Úsáideoir:MALA2009/Anne Frank (Béarla)

Annelies Marie "Anne" Frank (Teimpléad:Pronunciation) (12 June 1929 in Frankfurt am Main – early March 1945 in Bergen Belsen) was a Jewish girl who was born in the city of Frankfurt am Main in Weimar Germany, and who lived most of her life in or near Amsterdam, in the Netherlands. She gained international fame posthumously following the publication of her diary which documents her experiences hiding during the German occupation of the Netherlands in World War II.

Anne and her family moved to Amsterdam in 1933 after the Nazis gained power in Germany, and were trapped by the occupation of the Netherlands, which began in 1940. As persecutions against the Jewish population increased, the family went into hiding in July 1942 in hidden rooms in her father Otto Frank's office building. After two years, the group was betrayed and transported to concentration camps. Seven months after her arrest, Anne Frank died of typhus in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, within days of the death of her sister, Margot Frank. Her father Otto, the only survivor of the group, returned to Amsterdam after the war to find that her diary had been saved, and his efforts led to its publication in 1947. It was translated from its original Dutch and first published in English in 1952 as The Diary of a Young Girl.

The diary, which was given to Anne on her 13th birthday, chronicles her life from 12 June 1942 until 1 August 1944. It has been translated into many languages, has become one of the world's most widely read books, and has been the basis for several plays and films. Anne Frank has been acknowledged for the quality of her writing, and has become one of the most renowned and most discussed victims of the Holocaust.

Early life

[cuir in eagar | athraigh foinse]Annelies Marie "Anne" Frank was born on 12 June 1929 in Frankfurt, Germany, the second daughter of Otto Frank (1889–1980) and Edith Frank-Holländer (1900–45). Margot Frank (1926–45) was her elder sister.[1] The Franks were liberal Jews and lived in an assimilated community of Jewish and non-Jewish citizens, where the children grew up with Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish friends. The Frank family did not observe all of the customs and traditions of Judaism.[2] Edith Frank was the more devout parent, while Otto Frank, a decorated German officer from World War I, was interested in scholarly pursuits and had an extensive library; both parents encouraged the children to read.[3]

On 13 March 1933, elections were held in Frankfurt for the municipal council, and Adolf Hitler's Nazi Party won. Antisemitic demonstrations occurred almost immediately, and the Franks began to fear what would happen to them if they remained in Germany. Later that year, Edith and the children went to Aachen, where they stayed with Edith's mother, Rosa Holländer. Otto Frank remained in Frankfurt, but after receiving an offer to start a company in Amsterdam, he moved there to organise the business and to arrange accommodation for his family.[4] The Franks were among about 300,000 Jews who fled Germany between 1933 and 1939.[5]

Otto Frank began working at the Opekta Works, a company that sold the fruit extract pectin, and found an apartment on the Merwedeplein (Merwede Square) in Amsterdam. By February 1934, Edith and the children had arrived in Amsterdam, and the two girls were enrolled in school—Margot in public school and Anne in a Montessori school. Margot demonstrated ability in arithmetic, and Anne showed aptitude for reading and writing. Her friend Hanneli Goslar later recalled that from early childhood, Anne frequently wrote, though she shielded her work with her hands and refused to discuss the content of her writing. Margot and Anne had highly distinct personalities, Margot being well-mannered, reserved, and studious,[6] while Anne was outspoken, energetic, and extroverted.[7]

In 1938, Otto Frank started a second company Pectacon, which was a wholesaler of herbs, pickling salts and mixed spices, used in the production of sausages.[8][9] Hermann van Pels was employed by Pectacon as an advisor about spices. He was a Jewish butcher, who had fled Osnabrück in Germany with his family.[9] In 1939, Edith's mother came to live with the Franks, and remained with them until her death in January 1942.[10]

In May 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands, and the occupation government began to persecute Jews by the implementation of restrictive and discriminatory laws; mandatory registration and segregation soon followed. Margot and Anne were excelling in their studies and had many friends, but with the introduction of a decree that Jewish children could attend only Jewish schools, they were enrolled at the Jewish Lyceum.[10] In April 1941, Otto Frank took action to prevent Pectacon from being confiscated as a Jewish-owned business. He transferred his shares in Pectacon to Johannes Kleiman, and resigned as director. The company was liquidated and all assets transferred to Gies and Company, headed by Jan Gies. In December 1941, he followed a similar process to save Opekta. The businesses continued with little obvious change and their survival allowed Otto Frank to earn a minimal income, but sufficient to provide for his family.[11]

Time period chronicled in the diary

[cuir in eagar | athraigh foinse]Before going into hiding

[cuir in eagar | athraigh foinse]For her thirteenth birthday on 12 June 1942, Anne received a book she had shown her father in a shop window a few days earlier. Although it was an autograph book, bound with red-and-green plaid cloth and with a small lock on the front, Anne decided she would use it as a diary,[12] and began writing in it almost immediately. While many of her early entries relate the mundane aspects of her life, she also discusses some of the changes that had taken place in the Netherlands since the German occupation. In her entry dated 20 June 1942, she lists many of the restrictions that had been placed upon the lives of the Dutch Jewish population, and also notes her sorrow at the death of her grandmother earlier in the year.[13] Anne dreamed about becoming an actress. She loved watching movies, but the Dutch Jews were forbidden access to movie theaters beginning 8 January 1941.[14]

In July 1942, Margot Frank received a call-up notice from the Zentralstelle für jüdische Auswanderung (Central Office for Jewish Emigration) ordering her to report for relocation to a work camp. Anne was told by her father that the family would go into hiding in rooms above and behind the company's premises on the Prinsengracht, a street along one of Amsterdam's canals, where some of Otto Frank's most trusted employees would help them. The call-up notice forced them to relocate several weeks earlier than had been anticipated.[15]

Life in the Achterhuis

[cuir in eagar | athraigh foinse]

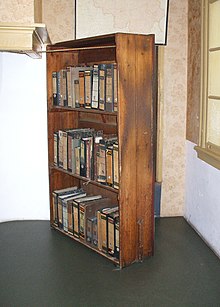

On the morning of Monday, 6 July 1942,[16] the family moved into the hiding place. Their apartment was left in a state of disarray to create the impression that they had left suddenly, and Otto Frank left a note that hinted they were going to Switzerland. The need for secrecy forced them to leave behind Anne's cat, Moortje. As Jews were not allowed to use public transport, they walked several kilometers from their home, with each of them wearing several layers of clothing as they did not dare to be seen carrying luggage.[17]The Achterhuis (a Dutch word denoting the rear part of a house, translated as the "Secret Annexe" in English editions of the diary) was a three-story space entered from a landing above the Opekta offices. Two small rooms, with an adjoining bathroom and toilet, were on the first level, and above that a larger open room, with a small room beside it. From this smaller room, a ladder led to the attic. The door to the Achterhuis was later covered by a bookcase to ensure it remained undiscovered. The main building, situated a block from the Westerkerk, was nondescript, old and typical of buildings in the western quarters of Amsterdam.[18]

Victor Kugler, Johannes Kleiman, Miep Gies, and Bep Voskuijl were the only employees who knew of the people in hiding, and with Gies's husband Jan Gies and Voskuijl's father Johannes Hendrik Voskuijl, were their "helpers" for the duration of their confinement. These contacts provided the only connection between the outside world and the occupants of the house, and they kept the occupants informed of war news and political developments. They catered for all of their needs, ensured their safety and supplied them with food, a task that grew more difficult with the passage of time. Anne wrote of their dedication and of their efforts to boost morale within the household during the most dangerous of times. All were aware that if caught they could face the death penalty for sheltering Jews.[19]

On 13 July, the Franks were joined by the van Pels family: Hermann, Auguste, and 16-year-old Peter, and then in November by Fritz Pfeffer, a dentist and friend of the family. Anne wrote of her pleasure at having new people to talk to, but tensions quickly developed within the group forced to live in such confined conditions. After sharing her room with Pfeffer, she found him to be insufferable and resented his intrusion,[20] and she clashed with Auguste van Pels, whom she regarded as foolish. She regarded Hermann van Pels and Fritz Pfeffer as selfish, particularly in regards to the amount of food they consumed.[21] Some time later, after first dismissing the shy and awkward Peter van Pels, she recognised a kinship with him and the two entered a romance. She received her first kiss from him, but her infatuation with him began to wane as she questioned whether her feelings for him were genuine, or resulted from their shared confinement.[22] Anne Frank formed a close bond with each of the helpers and Otto Frank later recalled that she had anticipated their daily visits with impatient enthusiasm. He observed that Anne's closest friendship was with Bep Voskuijl, "the young typist... the two of them often stood whispering in the corner."[23]

In her writing, Anne Frank examined her relationships with the members of her family, and the strong differences in each of their personalities. She considered herself to be closest emotionally to her father, who later commented, "I got on better with Anne than with Margot, who was more attached to her mother. The reason for that may have been that Margot rarely showed her feelings and didn't need as much support because she didn't suffer from mood swings as much as Anne did."[24] Anne and Margot formed a closer relationship than had existed before they went into hiding, although Anne sometimes expressed jealousy towards Margot, particularly when members of the household criticised Anne for lacking Margot's gentle and placid nature. As Anne began to mature, the sisters were able to confide in each other. In her entry of 12 January 1944, Anne wrote, "Margot's much nicer... She's not nearly so catty these days and is becoming a real friend. She no longer thinks of me as a little baby who doesn't count."[25]

Anne frequently wrote of her difficult relationship with her mother, and of her ambivalence towards her. On 7 November 1942 she described her "contempt" for her mother and her inability to "confront her with her carelessness, her sarcasm and her hard-heartedness," before concluding, "She's not a mother to me."[26] Later, as she revised her diary, Anne felt ashamed of her harsh attitude, writing: "Anne is it really you who mentioned hate, oh Anne, how could you?"[27] She came to understand that their differences resulted from misunderstandings that were as much her fault as her mother's, and saw that she had added unnecessarily to her mother's suffering. With this realization, Anne began to treat her mother with a degree of tolerance and respect.[28]

Margot and Anne each hoped to return to school as soon as they were able, and continued with their studies while in hiding. Margot took a shorthand course by correspondence in Bep Voskuijl's name and received high marks; She also kept a diary, however it is believed to be lost[fíoras?]. Most of Anne's time was spent reading and studying, and she regularly wrote and edited her diary entries. In addition to providing a narrative of events as they occurred, she wrote about her feelings, beliefs and ambitions, subjects she felt she could not discuss with anyone. As her confidence in her writing grew, and as she began to mature, she wrote of more abstract subjects such as her belief in God, and how she defined human nature.[29]

Anne aspired to become a journalist, writing in her diary on Wednesday, 5 April 1944:

| “ | I finally realized that I must do my schoolwork to keep from being ignorant, to get on in life, to become a journalist, because that’s what I want! I know I can write ..., but it remains to be seen whether I really have talent ...

And if I don’t have the talent to write books or newspaper articles, I can always write for myself. But I want to achieve more than that. I can’t imagine living like Mother, Mrs. van Daan and all the women who go about their work and are then forgotten. I need to have something besides a husband and children to devote myself to! ... I want to be useful or bring enjoyment to all people, even those I’ve never met. I want to go on living even after my death! And that’s why I’m so grateful to God for having given me this gift, which I can use to develop myself and to express all that’s inside me! When I write I can shake off all my cares. My sorrow disappears, my spirits are revived! But, and that’s a big question, will I ever be able to write something great, will I ever become a journalist or a writer? |

” |

—Anne Frank[30] | ||

She continued writing regularly until her final entry of August 1, 1944.

Arrest

[cuir in eagar | athraigh foinse]

On the morning of 4 August 1944, the Achterhuis was stormed by the German Security Police (Grüne Polizei) following a tip-off from an informer who was never identified.[31] Led by Schutzstaffel Oberscharführer Karl Silberbauer of the Sicherheitsdienst, the group included at least three members of the Security Police. The Franks, van Pelses and Pfeffer were taken to the Gestapo headquarters where they were interrogated and held overnight. On 5 August, they were transferred to the Huis van Bewaring (House of Detention), an overcrowded prison on the Weteringschans. Two days later they were transported to Westerbork. Ostensibly a transit camp, by this time more than 100,000 Jews had passed through it. Having been arrested in hiding, they were considered criminals and were sent to the Punishment Barracks for hard labor.[32]

Victor Kugler and Johannes Kleiman were arrested and jailed at the penal camp for enemies of the regime at Amersfoort. Kleiman was released after seven weeks, but Kugler was held in various work camps until the war's end.[33] Miep Gies and Bep Voskuijl were questioned and threatened by the Security Police but were not detained. They returned to the Achterhuis the following day, and found Anne's papers strewn on the floor. They collected them, as well as several family photograph albums, and Gies resolved to return them to Anne after the war. On 7 August 1944, Gies attempted to facilitate the release of the prisoners by confronting Silberbauer and offering him money to intervene, but he refused.[34]

Deportation and death

[cuir in eagar | athraigh foinse]On September 3,[35] the group was deported on what would be the last transport from Westerbork to the Auschwitz concentration camp, and arrived after a three-day journey. In the chaos that marked the unloading of the trains, the men were forcibly separated from the women and children, and Otto Frank was wrenched from his family. Of the 1,019 passengers, 549—including all children younger than fifteen—were sent directly to the gas chambers. Anne had turned fifteen three months earlier and was one of the youngest people to be spared from her transport. She was soon made aware that most people were gassed upon arrival, and never learned that the entire group from the Achterhuis had survived this selection. She reasoned that her father, in his mid-fifties and not particularly robust, had been killed immediately after they were separated.[36]

With the other females not selected for immediate death, Anne was forced to strip naked to be disinfected, had her head shaved and was tattooed with an identifying number on her arm. By day, the women were used as slave labor and Anne was forced to haul rocks and dig rolls of sod; by night, they were crammed into overcrowded barracks. Witnesses later testified that Anne became withdrawn and tearful when she saw children being led to the gas chambers, though other witnesses reported that more often she displayed strength and courage, and that her gregarious and confident nature allowed her to obtain extra bread rations for Edith, Margot and herself. Disease was rampant and before long, Anne's skin became badly infected by scabies. She and Margot were moved into an infirmary, which was in a state of constant darkness, and infested with rats and mice. Edith Frank stopped eating, saving every morsel of food for her daughters and passing her rations to them, through a hole she made at the bottom of the infirmary wall.[37]

On 28 October, selections began for women to be relocated to Bergen-Belsen. More than 8,000 women, including Anne and Margot Frank and Auguste van Pels, were transported, but Edith Frank was left behind and later died from starvation.[38] Tents were erected at Bergen-Belsen to accommodate the influx of prisoners, and as the population rose, the death toll due to disease increased rapidly. Anne was briefly reunited with two friends, Hanneli Goslar and Nanette Blitz, who were confined in another section of the camp. Goslar and Blitz both survived the war and later discussed the brief conversations that they had conducted with Anne through a fence. Blitz described her as bald, emaciated and shivering and Goslar noted that Auguste van Pels was with Anne and Margot Frank, and was caring for Margot, who was severely ill. Neither of them saw Margot as she was too weak to leave her bunk. Anne told both Blitz and Goslar that she believed her parents were dead, and for that reason did not wish to live any longer. Goslar later estimated that their meetings had taken place in late January or early February, 1945.[39]

In March 1945, a typhus epidemic spread through the camp and killed approximately 17,000 prisoners.[40] Witnesses later testified that Margot fell from her bunk in her weakened state and was killed by the shock, and that a few days later Anne died. They stated that this occurred a few weeks before the camp was liberated by British troops on 15 April 1945, although the exact dates were not recorded.[41][42] After liberation, the camp was burned in an effort to prevent further spread of disease, and Anne and Margot were buried in a mass grave, the exact whereabouts of which is unknown.

After the war, it was estimated that of the 107,000 Jews deported from the Netherlands between 1942 and 1944, only 5,000 survived. It was also estimated that up to 30,000 Jews remained in the Netherlands, with many people aided by the Dutch underground. Approximately two-thirds of these people survived the war.[43]

Otto Frank survived his internment in Auschwitz. After the war ended, he returned to Amsterdam where he was sheltered by Jan and Miep Gies, as he attempted to locate his family. He learned of the death of his wife, Edith, in Auschwitz, but he remained hopeful that his daughters had survived. After several weeks, he discovered that Margot and Anne also had died. He attempted to determine the fates of his daughters' friends, and learned that many had been murdered. Susanne Ledermann, often mentioned in Anne's diary, had been gassed along with her parents, though her sister, Barbara, a close friend of Margot, had survived.[44] Several of the Frank sisters' school friends had survived, as had the extended families of both Otto and Edith Frank, as they had fled Germany during the mid 1930s, with individual family members settling in Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States.

The Diary of a Young Girl

[cuir in eagar | athraigh foinse]Publication

[cuir in eagar | athraigh foinse]In July 1945, after the Red Cross confirmed the deaths of Anne and Margot, Miep Gies gave Otto Frank the diary, along with a bundle of loose notes that she had saved, in the hope that she could have returned them to Anne. Otto Frank later commented that he had not realised Anne had kept such an accurate and well-written record of their time in hiding. In his memoir he described the painful process of reading the diary, recognizing the events described and recalling that he had already heard some of the more amusing episodes read aloud by his daughter. He also noted that he saw for the first time the more private side of his daughter, and those sections of the diary she had not discussed with anyone, noting, "For me it was a revelation... I had no idea of the depth of her thoughts and feelings... She had kept all these feelings to herself".[45] Moved by her repeated wish to be an author, he began to consider having it published.

Anne's diary began as a private expression of her thoughts and she wrote several times that she would never allow anyone to read it. She candidly described her life, her family and companions, and their situation, while beginning to recognise her ambition to write fiction for publication. In March 1944, she heard a radio broadcast by Gerrit Bolkestein—a member of the Dutch government in exile—who said that when the war ended, he would create a public record of the Dutch people's oppression under German occupation.[46] He mentioned the publication of letters and diaries, and Anne decided to submit her work when the time came. She began editing her writing, removing sections and rewriting others, with the view to publication. Her original notebook was supplemented by additional notebooks and loose-leaf sheets of paper. She created pseudonyms for the members of the household and the helpers. The van Pels family became Hermann, Petronella, and Peter van Daan, and Fritz Pfeffer became Albert Düssell. In this edited version, she also addressed each entry to "Kitty," a fictional character in Cissy van Marxveldt's Joop ter Heul novels that Anne enjoyed reading. Otto Frank used her original diary, known as "version A", and her edited version, known as "version B", to produce the first version for publication. He removed certain passages, most notably those in which Anne is critical of her parents (especially her mother), and sections that discussed Anne's growing sexuality. Although he restored the true identities of his own family, he retained all of the other pseudonyms.

Otto Frank gave the diary to the historian Annie Romein-Verschoor, who tried unsuccessfully to have it published. She then gave it to her husband Jan Romein, who wrote an article about it, titled "Kinderstem" ("A Child's Voice"), published in the newspaper Het Parool on 3 April 1946. He wrote that the diary "stammered out in a child's voice, embodies all the hideousness of fascism, more so than all the evidence at Nuremberg put together"[47] His article attracted attention from publishers, and the diary was published in the Netherlands as Het Achterhuis in 1947,[48] followed by a second run in 1950.

It was first published in Germany and France in 1950, and after being rejected by several publishers, was first published in the United Kingdom in 1952. The first American edition was published in 1952 under the title Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl and was positively reviewed. It was successful in France, Germany and the United States, but in the United Kingdom it failed to attract an audience and by 1953 was out of print. Its most noteworthy success was in Japan where it received critical acclaim and sold more than 100,000 copies in its first edition. In Japan, Anne Frank quickly became identified as an important cultural figure who represented the destruction of youth during the war.[49]

A play based upon the diary, by Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett, premiered in New York City on 5 October 1955, and later won a Pulitzer Prize for Drama. It was followed by the 1959 movie The Diary of Anne Frank, which was a critical and commercial success. The biographer, Melissa Müller, later wrote that the dramatization had "contributed greatly to the romanticizing, sentimentalizing and universalizing of Anne's story."[50] Over the years the popularity of the diary grew, and in many schools, particularly in the United States, it was included as part of the curriculum, introducing Anne Frank to new generations of readers.

In 1986, the Netherlands State Institute for War Documentation published the "Critical Edition" of the diary. It includes comparisons from all known versions, both edited and unedited. It also includes discussion asserting its authentication, as well as additional historical information relating to the family and the diary itself.[51]

Cornelis Suijk—a former director of the Anne Frank Foundation and president of the U.S. Center for Holocaust Education Foundation—announced in 1999 that he was in the possession of five pages that had been removed by Otto Frank from the diary prior to publication; Suijk claimed that Otto Frank gave these pages to him shortly before his death in 1980. The missing diary entries contain critical remarks by Anne Frank about her parents' strained marriage, and discusses Anne's lack of affection for her mother.[52] Some controversy ensued when Suijk claimed publishing rights over the five pages and intended to sell them to raise money for his U.S. Foundation. The Netherlands Institute for War Documentation, the formal owner of the manuscript, demanded the pages to be handed over. In 2000, the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science agreed to donate US$300,000 to Suijk's Foundation, and the pages were returned in 2001. Since then, they have been included in new editions of the diary.

Reception

[cuir in eagar | athraigh foinse]The diary has been praised for its literary merits. Commenting on Anne Frank's writing style, the dramatist Meyer Levin commended Frank for "sustaining the tension of a well-constructed novel",[53] and was so impressed by the quality of her work that he collaborated with Otto Frank on a dramatisation of the diary shortly after its publication.[54] The poet John Berryman wrote that it was a unique depiction, not merely of adolescence but of the "conversion of a child into a person as it is happening in a precise, confident, economical style stunning in its honesty".[55]

In her introduction to the diary's first American edition, Eleanor Roosevelt described it as "one of the wisest and most moving commentaries on war and its impact on human beings that I have ever read". John F. Kennedy discussed Anne Frank in a 1961 speech, and said, "Of all the multitudes who throughout history have spoken for human dignity in times of great suffering and loss, no voice is more compelling than that of Anne Frank."[56] In the same year, the Soviet writer Ilya Ehrenburg wrote of her: "one voice speaks for six million—the voice not of a sage or a poet but of an ordinary little girl."[57]

As Anne Frank's stature as both a writer and humanist has grown, she has been discussed specifically as a symbol of the Holocaust and more broadly as a representative of persecution. Hillary Rodham Clinton, in her acceptance speech for an Elie Wiesel Humanitarian Award in 1994, read from Anne Frank's diary and spoke of her "awakening us to the folly of indifference and the terrible toll it takes on our young," which Clinton related to contemporary events in Sarajevo, Somalia and Rwanda.[58] After receiving a humanitarian award from the Anne Frank Foundation in 1994, Nelson Mandela addressed a crowd in Johannesburg, saying he had read Anne Frank's diary while in prison and "derived much encouragement from it." He likened her struggle against Nazism to his struggle against apartheid, drawing a parallel between the two philosophies with the comment "because these beliefs are patently false, and because they were, and will always be, challenged by the likes of Anne Frank, they are bound to fail."[59] Also in 1994, Václav Havel said that "Anne Frank's legacy is very much alive and it can address us fully" in relation to the political and social changes occurring at the time in former Eastern Bloc countries.[56]

Primo Levi suggested that Anne Frank is frequently identified as a single representative of the millions of people who suffered and died as she did because, "One single Anne Frank moves us more than the countless others who suffered just as she did but whose faces have remained in the shadows. Perhaps it is better that way; if we were capable of taking in all the suffering of all those people, we would not be able to live."[56] In her closing message in Melissa Müller's biography of Anne Frank, Miep Gies expressed a similar thought, though she attempted to dispel what she felt was a growing misconception that "Anne symbolises the six million victims of the Holocaust", writing: "Anne's life and death were her own individual fate, an individual fate that happened six million times over. Anne cannot, and should not, stand for the many individuals whom the Nazis robbed of their lives... But her fate helps us grasp the immense loss the world suffered because of the Holocaust."[60]

Otto Frank spent the remainder of his life as custodian of his daughter's legacy, saying, "It's a strange role. In the normal family relationship, it is the child of the famous parent who has the honor and the burden of continuing the task. In my case the role is reversed." He also recalled his publisher explaining why he thought the diary has been so widely read, with the comment "he said that the diary encompasses so many areas of life that each reader can find something that moves him personally".[61] Simon Wiesenthal later expressed a similar opinion when he said that Anne Frank's diary had raised more widespread awareness of the Holocaust than had been achieved during the Nuremberg Trials, because "people identified with this child. This was the impact of the Holocaust, this was a family like my family, like your family and so you could understand this."[62]

In June 1999, Time magazine published a special edition titled "Time 100: The Most Important People of the Century". Anne Frank was selected as one of the "Heroes & Icons", and the writer, Roger Rosenblatt, described her legacy with the comment, "The passions the book ignites suggest that everyone owns Anne Frank, that she has risen above the Holocaust, Judaism, girlhood and even goodness and become a totemic figure of the modern world—the moral individual mind beset by the machinery of destruction, insisting on the right to live and question and hope for the future of human beings." He also notes that while her courage and pragmatism are admired, it is her ability to analyze herself and the quality of her writing that are the key components of her appeal. He writes, "The reason for her immortality was basically literary. She was an extraordinarily good writer, for any age, and the quality of her work seemed a direct result of a ruthlessly honest disposition."[63]

Denials and legal action

[cuir in eagar | athraigh foinse]After the diary became widely known in the late 1950s, various allegations against the diary were published, with the earliest published criticisms occurring in Sweden and Norway. Among the accusations was a claim that the diary had been written by Meyer Levin,[64] and that Anne Frank had not really existed.

In 1958, Simon Wiesenthal was challenged by a group of protesters at a performance of The Diary of Anne Frank in Vienna who asserted that Anne Frank had never existed, and who challenged Wiesenthal to prove her existence by finding the man who had arrested her. He began searching for Karl Silberbauer and found him in 1963. When interviewed, Silberbauer readily admitted his role, and identified Anne Frank from a photograph as one of the people arrested. He provided a full account of events and recalled emptying a briefcase full of papers onto the floor. His statement corroborated the version of events that had previously been presented by witnesses such as Otto Frank.[65]

Opponents of the diary continued to express the view that it was not written by a child, but had been created as pro-Jewish propaganda, with Otto Frank accused of fraud. In 1959, Frank took legal action in Lübeck against Lothar Stielau, a school teacher and former Hitler Youth member who published a school paper that described the diary as a forgery. The complaint was extended to include Heinrich Buddegerg, who wrote a letter in support of Stielau, which was published in a Lübeck newspaper. The court examined the diary, and, in 1960, authenticated the handwriting as matching that in letters known to have been written by Anne Frank, and declared the diary to be genuine. Stielau recanted his earlier statement, and Otto Frank did not pursue the case any further.[64]

In 1976, Otto Frank took action against Heinz Roth of Frankfurt, who published pamphlets stating that the diary was a forgery. The judge ruled that if he published further statements he would be subjected to a fine of 500,000 German marks and a six-month jail sentence. Roth appealed against the court's decision and died in 1978, a year before his appeal was rejected.[64]

Otto Frank mounted a further lawsuit in 1976 against Ernst Römer who distributed a pamphlet titled "The Diary of Anne Frank, Bestseller, A Lie". When another man named Edgar Geiss distributed the same pamphlet in the courtroom, he too was prosecuted. Römer was fined 1,500 Deutschmarks,[64] and Geiss was sentenced to six months imprisonment. On appeal the sentence was reduced, but the case against him was dropped following a subsequent appeal because the statutory limitation for libel had expired.[66]

With Otto Frank's death in 1980, the original diary, including letters and loose sheets, were willed to the Dutch Institute for War Documentation,[67] who commissioned a forensic study of the diary through the Netherlands Ministry of Justice in 1986. They examined the handwriting against known examples and found that they matched, and determined that the paper, glue and ink were readily available during the time the diary was said to have been written. Their final determination was that the diary is authentic, and their findings were published in what has become known as the "Critical Edition" of the diary. On 23 March 1990, the Hamburg Regional Court confirmed its authenticity.[51]

In 1991, Holocaust deniers Robert Faurisson and Siegfried Verbeke produced a booklet titled The Diary of Anne Frank: A Critical Approach. They claimed that Otto Frank wrote the diary, based on assertions that the diary contained several contradictions, that hiding in the Achterhuis would have been impossible, and that the prose style and handwriting of Anne Frank were not those of a teenager.[68]

The Anne Frank House in Amsterdam and the Anne Frank Funds in Basel instigated a civil law suit in December 1993, to prohibit the further distribution of The Diary of Anne Frank: A Critical Approach in the Netherlands. On 9 December 1998, the Amsterdam District Court ruled in favour of the claimants, forbade any further denial of the authenticity of the diary and unsolicited distribution of publications to that effect, and imposed a penalty of 25,000 guilders per infringement.[69]

Legacy

[cuir in eagar | athraigh foinse]

On 3 May 1957, a group of citizens, including Otto Frank, established the Anne Frank Stichting in an effort to rescue the Prinsengracht building from demolition and to make it accessible to the public. The Anne Frank House opened on 3 May 1960. It consists of the Opekta warehouse and offices and the Achterhuis, all unfurnished so that visitors can walk freely through the rooms. Some personal relics of the former occupants remain, such as movie star photographs glued by Anne to a wall, a section of wallpaper on which Otto Frank marked the height of his growing daughters, and a map on the wall where he recorded the advance of the Allied Forces, all now protected behind Perspex sheets. From the small room which was once home to Peter van Pels, a walkway connects the building to its neighbours, also purchased by the Foundation. These other buildings are used to house the diary, as well as changing exhibits that chronicle different aspects of the Holocaust and more contemporary examinations of racial intolerance in various parts of the world. It has become one of Amsterdam's main tourist attractions, and in 2005 received a record 965,000 visitors. The House provides information via the internet, as well as travelling exhibitions, for those not able to visit. In 2005, exhibitions travelled to 32 countries in Europe, Asia, North America and South America.[70]

In 1963, Otto Frank and his second wife, Elfriede Geiringer-Markovits, set up the Anne Frank Fonds as a charitable foundation, based in Basel, Switzerland. The Fonds raises money to donate to causes "as it sees fit". Upon his death, Otto willed the diary's copyright to the Fonds, on the provision that the first 80,000 Swiss francs in income each year was to be distributed to his heirs, and any income above this figure was to be retained by the Fonds to use for whatever projects its administrators considered worthy. It provides funding for the medical treatment of the Righteous among the Nations on a yearly basis. It has aimed to educate young people against racism and has loaned some of Anne Frank's papers to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. for an exhibition in 2003. Its annual report of the same year gave some indication of its effort to contribute on a global level, with its support of projects in Germany, Israel, India, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States.[71]

The Merwedeplein apartment, in which the Frank family lived from 1933 until 1942, remained privately owned until the early 2000s, when a television documentary focused public attention upon it. In a serious state of disrepair, it was purchased by a Dutch housing corporation, and aided by photographs taken by the Frank family and descriptions of the apartment and furnishings in letters written by Anne Frank, was restored to its 1930s appearance. Teresien da Silva of the Anne Frank House, and Anne Frank's cousin Bernhard "Buddy" Elias also contributed to the restoration project. It opened in 2005 with the aim of providing a safe haven for a selected writer who is unable to write freely in his or her own country. Each selected writer is allowed one year's tenancy during which to reside and work in the apartment. The first writer selected was the Algerian novelist and poet, El-Mahdi Acherchour.[70]

In June 2007, "Buddy" Elias donated some 25,000 family documents to the Anne Frank House. Among the artifacts are Frank family photographs taken in Germany and Holland and the letter Otto Frank sent his mother in 1945 informing her that his wife and daughters had perished in Nazi concentration camps.[72]

In November 2007, the Anne Frank tree was scheduled to be cut down to prevent it from falling down on one of the surrounding buildings, after a fungal disease had affected the trunk of this horse-chestnut tree. Dutch economist Arnold Heertje, who was also in hiding during the Second World War,[73] said about the tree: "This is not just any tree. The Anne Frank tree is bound up with the persecution of the Jews."[74] The Tree Foundation, a group of tree conservationists, started a civil case in order to stop the felling of the horse chestnut, which received international media attention. A Dutch court ordered the city officials and conservationists to explore alternatives and come to a solution.[75] The parties agreed to build a steel construction that would prolong the life of the tree up to 15 years.[74]

Over the years, several films about Anne Frank appeared and her life and writings have inspired a diverse group of artists and social commentators to make reference to her in literature, popular music, television, and other forms of media. In 1999, Time named Anne Frank among the heroes and icons of the 20th century on their list The Most Important People of the Century, stating: "With a diary kept in a secret attic, she braved the Nazis and lent a searing voice to the fight for human dignity".[76]

See also

[cuir in eagar | athraigh foinse]Notes and references

[cuir in eagar | athraigh foinse]- ↑ Müller, Family tree, preface to Chapter One

- ↑ Van der Rol and Verhoeven, p. 10

- ↑ Lee, p. 17

- ↑ Lee, pp. 20–23

- ↑ Van der Rol and Verhoeven, p. 21

- ↑ Müller, p. 131

- ↑ Müller, pp. 129–35

- ↑ Müller, p. 92

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Lee, p. 40

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Müller, pp. 128–130

- ↑ Müller, pp. 117-118

- ↑ Lee, p. 96

- ↑ Frank and Massotty, pp. 1–20

- ↑ Müller, Melissa. Anne Frank: The Biography Macmillan, 1998. ISBN 0-8050-5996-2 pp. 119-120

- ↑ Müller, p. 153

- ↑ Müller, p. 163

- ↑ Lee, pp. 105–106

- ↑ Westra, pp. 45 and 107–187

- ↑ Lee, pp. 113–115

- ↑ Lee, pp. 120–21

- ↑ Lee, p. 117

- ↑ Westra, p. 191

- ↑ Lee, p. 119

- ↑ Müller, p. 203

- ↑ Frank and Massotty, p. 167

- ↑ Frank and Massotty, p. 63

- ↑ Frank and Massotty, p. 157

- ↑ Müller, p. 204

- ↑ Müller, p. 194

- ↑ [1] Lessons from The Diary of Anne Frank by Harold Marcuse, UCSB

- ↑ Tá ort na shonrú' 'teideal = agus' 'url = nuair a úsáideann {{ lua idirlín}}."" (PDF).

- ↑ Müller, p. 233

- ↑ Müller, p. 291

- ↑ Müller, p. 279

- ↑ Westra, p. 196 includes a reproduction of part of the transport list showing the names of each of the Frank family

- ↑ Müller, pp. 246–247

- ↑ Müller, pp. 248–251

- ↑ Müller, p. 252

- ↑ Müller, p. 255

- ↑ Müller, p. 261

- ↑ Tá ort na shonrú' 'teideal = agus' 'url = nuair a úsáideann {{ lua idirlín}}."" (2003).

- ↑ Tá ort na shonrú' 'teideal = agus' 'url = nuair a úsáideann {{ lua idirlín}}."". Betrayed 5.

- ↑ Tá ort na shonrú' 'teideal = agus' 'url = nuair a úsáideann {{ lua idirlín}}."".

- ↑ Lee, pp. 211–212

- ↑ Lee, p. 216

- ↑ Frank and Massotty, p. 242

- ↑ Tá ort na shonrú' 'teideal = agus' 'url = nuair a úsáideann {{ lua idirlín}}."".

- ↑ Lee, p. 223

- ↑ Lee, p. 225

- ↑ Müller, p. 276

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Frank, Anne and Netherlands State Institute for War Documentation, p. 102

- ↑ Tá ort na shonrú' 'teideal = agus' 'url = nuair a úsáideann {{ lua idirlín}}."".

- ↑ Tá ort na shonrú' 'teideal = agus' 'url = nuair a úsáideann {{ lua idirlín}}."".

- ↑ Michaelsen, Jacob B. "Remembering Anne Frank". Judaism (Spring 1997). Retrieved on 17 March 2006.

- ↑ Berryman, John. "The Development of Anne Frank" in Solotaroff-Enzer, Sandra and Hyman Aaron Enzer (2000). "Anne Frank: Reflections on her life and legacy". Univ. of Illinois Press.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 Westra, p. 242

- ↑ Tá ort na shonrú' 'teideal = agus' 'url = nuair a úsáideann {{ lua idirlín}}."". Yale Holocaust Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Remarks by the First Lady, Elie Wiesel Humanitarian Awards, New York City. Clinton4.nara.gov, 14 April 1994. Retrieved on 2007-12-02.

- ↑ Address by President Nelson Mandela at the Johannesburg opening of the Anne Frank exhibition at the Museum Africa. African National Congress, 15 August 1994. Retrieved on 2007-12-02.

- ↑ Müller, p. 305

- ↑ Lee, pp. 222–33

- ↑ Tá ort na shonrú' 'teideal = agus' 'url = nuair a úsáideann {{ lua idirlín}}."".

- ↑ Tá ort na shonrú' 'teideal = agus' 'url = nuair a úsáideann {{ lua idirlín}}."".

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 64.3 Tá ort na shonrú' 'teideal = agus' 'url = nuair a úsáideann {{ lua idirlín}}."".

- ↑ Lee, pp. 241–246

- ↑ Tá ort na shonrú' 'teideal = agus' 'url = nuair a úsáideann {{ lua idirlín}}."".

- ↑ Lee, p. 233

- ↑ Tá ort na shonrú' 'teideal = agus' 'url = nuair a úsáideann {{ lua idirlín}}."".

- ↑ Tá ort na shonrú' 'teideal = agus' 'url = nuair a úsáideann {{ lua idirlín}}."".

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Tá ort na shonrú' 'teideal = agus' 'url = nuair a úsáideann {{ lua idirlín}}."" (PDF).

- ↑ Tá ort na shonrú' 'teideal = agus' 'url = nuair a úsáideann {{ lua idirlín}}."".

- ↑ Tá ort na shonrú' 'teideal = agus' 'url = nuair a úsáideann {{ lua idirlín}}."". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Tá ort na shonrú' 'teideal = agus' 'url = nuair a úsáideann {{ lua idirlín}}."". nrc•next.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Tá ort na shonrú' 'teideal = agus' 'url = nuair a úsáideann {{ lua idirlín}}."". www.reuters.com.

- ↑ Tá ort na shonrú' 'teideal = agus' 'url = nuair a úsáideann {{ lua idirlín}}."". www.reuters.com.

- ↑ Tá ort na shonrú' 'teideal = agus' 'url = nuair a úsáideann {{ lua idirlín}}."". The Time 100.

Bibliography

[cuir in eagar | athraigh foinse]- Frank, Anne; Massotty, Susan (translation); Frank, Otto H. & Pressler, Mirjam (editors) (1995). The Diary of a Young Girl - The Definitive Edition. Doubleday. ISBN 0-553-29698-1. (This edition, a new translation, includes material excluded from the earlier edition.)

- Frank, Anne and Netherlands State Institute for War Documentation (1989). The Diary of Anne Frank, The Critical Edition. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-24023-6.

- Lee, Carol Ann (2000). The Biography of Anne Frank - Roses from the Earth. Viking. ISBN 0-7089-9174-2.

- Müller, Melissa; Kimber, Rita; Kimber, Robert (translators); With a note from Miep Gies (2000). Anne Frank - The Biography. Metropolitan books. ISBN 0-7475-4523-5.

- van der Rol, Ruud; Verhoeven, Rian (for the Anne Frank House); Quindlen, Anna (Introduction); Langham, Tony & Peters, Plym (translation) (1995). Anne Frank - Beyond the Diary - A Photographic Remembrance. Puffin. ISBN 0-14-036926-0.

- Westra, Hans; Metselaar, Menno; Van Der Rol, Ruud; Stam, Dineke (2004). Inside Anne Frank's House: An Illustrated Journey Through Anne's World. Overlook Duckworth. ISBN 1-58567-628-4.

External links

[cuir in eagar | athraigh foinse]- Anne Frank House

- Anne Frank-Fonds (Foundation)

- Anne Frank Center, USA

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum - Exhibition "Anne Frank: An Unfinished Story" and Encyclopedia Anne Frank

- BBC: The Diary of Anne Frank

Teimpléad:Persondata

Category:Bergen-Belsen concentration camp victims

Category:Child writers

Category:Children who died in Nazi concentration camps

Category:Deaths from typhus

Category:Dutch diarists

Category:Dutch people of World War II

Category:Dutch women writers

Category:German Jews

Category:German diarists

Category:German women writers

Category:Jewish refugees

Category:Jewish women writers

Category:People from Amsterdam

Category:People from Frankfurt

Category:Stateless persons

Category:Women diarists

Category:Women in World War II

Category:Writers who died in Nazi concentration camps

Teimpléad:Lifetime